How the Science of Fear Makes Soldiers Stronger

The U.S. military turns to science as it seeks new ways to create more resilient fighters and prevent PTSD.

By Kathryn Wallace from Reader's Digest | February 2013 It’s 2 a.m. on the Navy destroyer USS Trayer, and the air is thick with the smell of fuel and 350 sweaty recruits who have been working too many hours. It’s another long, monotonous shift of routine maintenance when, suddenly, the night is ripped open by the piercing wail of an emergency alarm.

It’s 2 a.m. on the Navy destroyer USS Trayer, and the air is thick with the smell of fuel and 350 sweaty recruits who have been working too many hours. It’s another long, monotonous shift of routine maintenance when, suddenly, the night is ripped open by the piercing wail of an emergency alarm.The Trayer is under attack. Explosions rock the ship as fires burn and the anguished cries of the injured fill the air. To escape the flames, the flooding, and the thick smoke, the men and women of the crew scramble through mangled compartments past gruesomely torn bodies. Lights flicker, turbines whine, metal rips, and the relentless scream of the alarm tells everyone what they already know: This is war.

Except it’s not.

As the recruits battle flame and rising waters and treat the wounded, Naval petty officers stand by, observing and evaluating the performance. The officers can remain almost eerily unflustered amid the chaos because the attack, and the ship itself, are simulated.

Dubbed the unluckiest ship in the Navy, the USS Trayer is under siege nearly every day at its mooring in a 90,000-gallon tank inside a cavernous building at the Recruit Training Command in Illinois. This long night of fire and flood—the exercise lasts 12 hours and runs through 17 different scenarios—is the elaborate and exhausting culmination of eight weeks of training. Every year, 37,000 recruits are subjected to the high-tech terror of the Trayer.

“This is supposed to feel real,” says Michael Belanger, PhD, a Navy senior psychologist, who headed the team that designed the $60 million landlocked ship. “This is supposed to scare the recruits.”

Mission accomplished. After his night in hell, Seaman Recruit Colt Bailey emerges from the Trayer weary and streaked with soot. “We were all scared and stressed out,” says Bailey, who boarded the Trayer for training last summer and panicked when he had to step into smoke so thick, he couldn’t see. But the 20-year-old from Eagle, Idaho, fought through his fear and kept going. Weeks of study—how to fight fire, how to move the wounded—had left him more prepared than he knew. “I learned I can trust my training,” he says. “I know there will be other times when it’s real, when it goes a step further, and I’ll be scared. In that moment, I hope I do what I did on the Trayer.”

The military counts on it. Each branch uses high-tech simulations: Battlemind (now called Resilience Training) is an Army and Marine Corps exercise in which troops inside a Humvee experience an IED attack and firefight. These exercises do more than train scared recruits to function amid the chaos and destruction of combat. They also serve as a kind of boot camp introduction to the potentially damaging effects of fear and anxiety. Among the worst of these, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—the crippling constellation of flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and other symptoms—today afflicts some 300,000 combat veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“PTSD is the signature wound of these wars,” says Paul Lester, PhD, an Army research psychologist. And the Department of Defense (DOD) has been waging an all-out offensive against it. Much of the multibranch, billion-dollar effort is focused on developing effective treatments for those already diagnosed. But the DOD also wants to prevent PTSD and has turned to brain science for answers. The ultimate goal: to create more mentally resilient soldiers and sailors, combatants armed with what one DOD-funded researcher calls warrior brains.

“Fear is the enemy,” says Comdr. Eric Potterat, PhD, a Navy Special Warfare group psychologist. The mental stress of war has claimed more casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan than bombs and bullets. “Psychological trauma can have profound negative effects on brain function,” says James B. Lohr, MD, who spent 12 years as chief of psychiatry at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in San Diego.

“Fear is the enemy,” says Comdr. Eric Potterat, PhD, a Navy Special Warfare group psychologist. The mental stress of war has claimed more casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan than bombs and bullets. “Psychological trauma can have profound negative effects on brain function,” says James B. Lohr, MD, who spent 12 years as chief of psychiatry at the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in San Diego.Fear should be our best friend. It’s a chemical reaction, a signal to pay attention to a threat. It’s our brain alerting us to danger, triggering the classic fight-or-flight response—sweaty palms, dry mouth, an increase in breathing and heart rate, a jolt of adrenalin—to help us survive. But when the brain doesn’t return to normal after a stressful incident, or when there are too many incidents, this hormone-driven alert system can turn toxic. The nature of our post-9/11 conflicts—enemy combatants embedded among civilian populations, using unconventional tactics and weapons like IEDs—has been especially hard on soldiers, says Lester: “They are in combat more frequently, with an enemy that uses terror as a weapon.” To Lester, recent military practice—like troops serving multiple combat tours with little time in between to recover—is practically a formula for creating PTSD.

The Inner Warrior

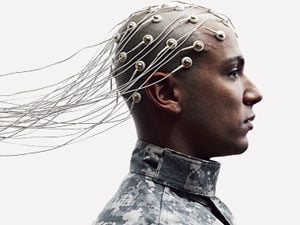

To understand what goes wrong in the brains of combat veterans who develop PTSD, and to try to prevent it from happening to others, neurobiologist Lilianne Mujica-Parodi, PhD, has spent years tossing volunteers with sensors all over their bodies out of airplanes. Her Navy-funded research measures physical fear responses, comparing sheer fright factors to the results of mental-processing tests she administers before, during, and after the skydiving flight.

To understand what goes wrong in the brains of combat veterans who develop PTSD, and to try to prevent it from happening to others, neurobiologist Lilianne Mujica-Parodi, PhD, has spent years tossing volunteers with sensors all over their bodies out of airplanes. Her Navy-funded research measures physical fear responses, comparing sheer fright factors to the results of mental-processing tests she administers before, during, and after the skydiving flight.Mujica-Parodi has discovered that in most cases, the brain does some predictable things when a human jumps out of a perfectly good airplane. Stress hormones flood the fear-response system, and thoughts narrowly focus on one thing: getting out of the air and onto the ground.

There are, however, the unflappable few subjects who don’t experience this wild swing of mental and physical reactions. They demonstrate some of their clearest thinking in the middle of a plunge, and when it’s over, their fear-response systems quickly return to normal.

“You don’t want someone without a fear response at all,” Mujica-Parodi says. “That’s not brave; that’s just abnormal. But a high stress response is also unhealthy.” The optimal fear response, she says, accurately assesses risk, saves room for cognitive thought, and rapidly returns to baseline when the danger passes. Brains that can do this are a gift of DNA, according to Mujica-Parodi, what she calls warrior brains. The soldiers who possess them benefit from an ideal balance of neurological and biological responses.

Using brain scans, Mujica-Parodi has seen how the fear-response system “cools down” faster in warrior brains than it does in the brains of more vulnerable subjects.

While her research is still experimental, Mujica-Parodi maintains that it’s now possible to identify someone with either a warrior brain or a vulnerability to stress disorders with the same certainty that we can diagnose an increased risk for diabetes. She envisions a day in the future when a brain scan will be part of military training, though there are no plans in any branch for such screening, which would surely raise a host of ethical issues. “You wouldn’t accept someone in Special Forces if he had weak legs,” she says. “Soon we’ll be able to screen people for emotional weaknesses. A person with an incapacitating fear response is a danger to himself, his team, and the mission.”

Lessons from the SEALsIdentifying the most resilient members of the U.S. military has been the business of the Navy SEALs for the past 50 years. Just to earn the right to try out for the legendary program, a candidate must be exceptionally tough, in body and mind. The chosen few must then survive up to 18 months of training so physically and mentally arduous that nearly 80 percent of this superior group of sailors never get past the fourth week.

So who makes it, and who washes out? The answer lies not in biceps size or speed but in a cognitive test the would-be SEALs take on induction day. The test measures 24 different personality traits, but the results of the “adversity tolerance” section, which explores how the candidates respond to extreme stress, are what best predicts who makes the cut.

“There are people who make a negative loop about the situation they are placed in,” says Potterat, the SEAL psychologist. “Those are people who can’t cope.” It’s the people who take control of stressful challenges “in any environment,” he says, who will eventually wear the SEAL uniform.

“Clearly something Darwinian is happening with the SEALs,” adds Potterat. “These are exceptional human beings.” Nevertheless, it’s the intense stress-management training, he says, that turns a tough sailor into a SEAL. Weeding out the less resilient candidates is just the first step.

Potterat describes the classified SEAL training program as highly mental. It uses techniques you can find in self-help books, such as breathing exercises that reset the fear system, calming self-talk, and compartmentalization of trauma until the job is done. Of course, SEAL candidates have to apply these methods while sleep-deprived and physically exhausted, during live-fire combat exercises; and much of the SEAL training is performed underwater, with instructors intentionally creating obstacles and cutting off the air supply to panic the recruits.

“Our training is all about worst-case scenarios and pushing us to the limits,” says Lu Lastra, director of mentorship for Naval Special Warfare and a 30-year veteran of the program. “You stand a much better chance of mentally withstanding war if you can visualize it and prepare your brain for it than if you’ve never thought of it, never been able to picture it.” The proof is in the numbers; it’s very rare for a SEAL to be diagnosed with PTSD.

Testing Stress

While some brains are naturally more resistant to stress than others, recent research on Marines diagnosed with PTSD suggests that vulnerable and even traumatized brains can be trained to manage fear more effectively. Martin Paulus, MD, a psychiatrist at UC San Diego who has studied the optimal stress responses in SEALs and elite athletes, wondered if resilience was akin to a muscle in the brain that, like all muscles, could be strengthened.

While some brains are naturally more resistant to stress than others, recent research on Marines diagnosed with PTSD suggests that vulnerable and even traumatized brains can be trained to manage fear more effectively. Martin Paulus, MD, a psychiatrist at UC San Diego who has studied the optimal stress responses in SEALs and elite athletes, wondered if resilience was akin to a muscle in the brain that, like all muscles, could be strengthened.“People who have resiliency respond to stressful events in a positive way,” says Paulus, who also works at the VA Healthcare System in San Diego. Paulus developed a mental fitness program for a test group of 20 Marine combat veterans with damaged stress responses. Rather than trying to blunt the fear they still carried from their battlefield experiences, Paulus intentionally stressed them, restricting their breathing and showing them unpleasant images, such as close-ups of angry faces, while observing their brain functions with a scanner. He likens this to testing knee reflexes with a hammer; the only way to test the fear system is to swing the hammer and apply some stress.

Paulus makes the combat vets uncomfortable to help them relearn that anxiety does not equal mortal danger. “The big issue with PTSD,” he says, “is that the brain still links up strong emotional responses to that experience of battle, triggering a cascade of stress responses that were helpful in battle but not now, in real life.”

After initial brain scans showed the Marines “overresponding” to the negative images and other stressors, Paulus put them through an eight-week mindfulness course. The program included “refocusing exercises” in which the vets were taught to mentally recast their traumatic battlefield memories and treat them simply as feelings or as obstacles to overcome. They also learned controlled breathing, meditation, and other relaxation techniques.

Early results from follow-up testing and scans point to improved resiliency among the Marines, or something closer to the warrior brain response, with a less reactive stress circuit and more control from the cognitive part of the brain. “This isn’t a new idea,” Paulus says, citing a historical precedent. “Samurai warriors famously used meditation, likely to balance the experiences of war.”

Science Makes Soldiers

While some of the research the U.S. military has commissioned suggests that there are those who simply do not belong in the armed forces, it adamantly believes that good soldiers and sailors are made, not born. That’s why it has spent millions rebooting boot camp and basic training to include high-tech simulations like the Trayer and Battlemind that closely mirror the chaos of the battlefield. “We have always been of the mind-set that we can make a good sailor out of anyone who comes through that front gate,” says Michael Belanger.

While some of the research the U.S. military has commissioned suggests that there are those who simply do not belong in the armed forces, it adamantly believes that good soldiers and sailors are made, not born. That’s why it has spent millions rebooting boot camp and basic training to include high-tech simulations like the Trayer and Battlemind that closely mirror the chaos of the battlefield. “We have always been of the mind-set that we can make a good sailor out of anyone who comes through that front gate,” says Michael Belanger.And science supports the idea. Huda Akil, PhD, who studies the neurobiology of fear and anxiety for the Navy at the University of Michigan, has coaxed resilience and “hardiness” from the most timid animals. Akil works with rats, which have a stress response somewhat similar to our own; they either cower and hide or become aggressive and proactive. “This is genetically predetermined,” Akil says. “We can breed curious, brave rats or timid, anxious rats. And after a few generations, they are very predictively one way or the other.”

But Akil found she could make an anxious rat braver by slightly stressing the animal. Making males fight or enriching the environment, with a toy, for example, can change them from timid to curious. “The brain is very plastic,” she says. “We found we can’t encourage a timid rat to be a high-risk taker, but we can move him off the timid side of the scale into average territory.”

The War on Fear

Back on the Trayer, the attack continues. Operating from a command center in the belly of the vessel, special effects engineers orchestrate the sights, sounds, and smells of naval warfare, pressing buttons to create explosions and fires and to trigger the screams of the wounded. Ceiling fans blow ocean-scented breezes, and recordings of gull cries echo above the bridge. Inside the ship, scattered around a blasted hull modeled after the real-life bombing of the USS Cole, mangled mannequins, wired for sound, call for help in the eerie red glare of the emergency lights.

Back on the Trayer, the attack continues. Operating from a command center in the belly of the vessel, special effects engineers orchestrate the sights, sounds, and smells of naval warfare, pressing buttons to create explosions and fires and to trigger the screams of the wounded. Ceiling fans blow ocean-scented breezes, and recordings of gull cries echo above the bridge. Inside the ship, scattered around a blasted hull modeled after the real-life bombing of the USS Cole, mangled mannequins, wired for sound, call for help in the eerie red glare of the emergency lights.It all seems so real, as if it were an actual maritime siege. But it’s not. Except for the enemy, that is. The enemy—fear—is real.

More On The USS Trayer (Battle Stations 21)

0 comments:

Post a Comment